In a word: no.

In six words: no, it couldn’t, and it doesn’t.

Yesterday, The Guardian reported on a study conducted by Luo and others, and suggested that the they “found compelling evidence that addressing these things [drinking champagne, and 55 other non-clinical risk factors] could prevent a large number of cases” of sudden cardiac arrest.

My BlueSky feed was full of epidemiologists decrying this research, and this interpretation. And they’re, of course, right to do so: it’s facile drek that adds nothing. At heart, it’s a waste of resources.

The study used UK Biobank data to conduct both observational and Mendelian Randomization analyses to get their results. I happen to have used UK Biobank data to conduct both observational and Mendelian Randomization analyses, so feel both confident I can critique what they did, and irritated I have to do so.

Study methods

UK Biobank is pretty cool: 500,000 people in the UK gave researchers baseline measurements of loads of things between 2006 and 2010, and they’ve been followed up since. Their data was tied to NHS records, so we have a fairly good idea of what happened to most of them (private healthcare usage aside) (also primary care records aren’t perfect: primary care in the UK decided, somehow, to all use competing electronic healthcare record systems, so there’s no unified database of primary care records. I find this infuriating).

The authors had data on basically everyone in UK Biobank until 31 December 2022, so a pretty decent window of observation.

Diagnosis of sudden cardiac arrest (your heart stopping, suddenly) was through an International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 code: I’m reasonably fine with this (ICD is absolutely fine, love it, though they may miss some earlier ICD-9 codes – last time I used UK Biobank NHS data, I needed both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to be complete. But whatever, that’s the least of my concerns.

The authors then whittled down the 28,859 variables recorded in UK Biobank to 125 “modifiable” exposure variables. That is, 125 things measured in almost all people in UK Biobank that were related to “lifestyle, psychosocial factors, local environment, physical measures, socioeconomic status, and early life risk factors”. Note that the title of the paper starts with “Modifiable risk factors” – we’ll see if they’re “modifiable” later.

The authors impute missing data using a technique called multiple imputation by chained equations. Great, happy with that, it’s what I would have done: this gets around having to kick out people from the analysis because of missing data, and usually (though not always) reduces the risk of bias due to missing data. It is substantially better than other forms of dealing with missing data. They didn’t use a single model to do it, and only included variables correlated with each exposure that was missing data – not sure why this was necessary, there’s enough people included in the analysis I would have been happy putting all variables into the same model, but I doubt it’s an issue.

The authors then prune the 125 exposures down to 56: these were the 56 exposures that were statistically significantly associated with sudden cardiac arrest on Cox proportional hazards regression, and weren’t colinear with each other – that is, one exposure in each pair of highly related exposures (think weight and body-mass index, where as one increases, so does the other one, virtually all the time) was kicked out, the other kept. Cox regression looks at how the exposures are associated with sudden cardiac arrest over time: if presence of the exposure increases the risk over time for sudden cardiac arrest, the hazard ratio (HR, the effect estimate from a Cox regression) is more than 1 (exposure = bad), if the risk of lower, the HR is less than 1 (exposure = good).

The authors used a Bonferroni correction to account for multiple testing when deciding what they meant by “statistically significant”: this is fine, all it does it make it a bit easier for exposures to be kicked out of the analysis at this stage. Since there’s 500,000 people in UK Biobank, statistical significance is extremely likely with a huge number of exposures, simply because there’s so much data. Reducing what they consider to be statistically significance from 0.05 to 0.0004 is not too problematic: it’s common practice when running a bunch of analyses at the same time.

Selecting variables based on statistical significance, I think, is problematic, but whatever. This, again, isn’t the main problem with what’s going on here.

Analyses: Mendelian randomization

The authors did two main analyses, in addition to the Cox regression: Mendelian randomization and population attributable risk. They start with Mendelian randomization, and so shall I.

Note: I won’t go through exactly what a Mendelian randomization analysis entails. If interested, we did a primer on making sense of Mendelian randomization and its use in health research.

The Mendelian randomization analysis was fine. They did two-sample Mendelian randomization, which is where you… argh, this is going to take some explanation. You start with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are point changes in your DNA code that might change your propensity toward something, for example, some SNPs predict your body mass index, some your height, some your risk of prostate cancer: it’s genetics, but it’s less clear cut than genetically-determined diseases like cystic fibrosis. You then see which SNPs are statistically significantly associated with your exposure using one dataset (here, UK Biobank, thanks to the good folks in Bristol IEU), and see how those same SNPs are associated with the outcome in a different dataset here, the Finnish Genome Research Project).

If your SNPs that are associated with, say, height are also associated with sudden cardiac arrest, you may well think that height might affect your risk of sudden cardiac arrest.

Fundamentally, this rests on a few assumptions, chief among them being that the SNPs only affect the exposure directly, and not the outcome directly. That is, the SNP can’t be doing two things. This is always an assumption (it can be tested, but not proven to be true), and to my mind, works best with exposures that are as close to single proteins as possible: if you have a SNP is a gene that codes a specific protein, chances are, it’s only affecting that protein. If you start looking at SNPs that are associated with complex behaviours, like, say, the likelihood you drink white wine or champagne, any associated SNPs might be affecting the outcome in ways other than through your exposure.

(Note: I’m aware that there are SNPs that predict teetotalism [those in the ADH gene], but that’s a different exposure to specific alcoholic drink intake [which will, I think, but socially patterned in people of White European ancestry more than genetically determined], and will potentially have other issues with ancestry.)

When this happen, your Mendelian randomization is useless for causality.

I would be super suspicious of anyone claiming causality on the basis of a Mendelian randomization analysis for lifestyle exposure, because the assumptions inherent in Mendelian randomization just won’t be met.

Anyway, their Mendelian randomization methods looked fine (although, see above…) – they did the same stuff I would have done, more or less.

Note: the authors use the term EWAS in the paper, meaning exposome-wide association study. This is a pretentious name for “putting a bunch of exposures into a model and seeing what happens” – it has no broader meaning than this. It isn’t fancy.

Analyses: Population attributable risk

I haven’t done population attributable risk, so far as I remember, so I won’t comment on whether the methods were appropriate. I’ll assume they were: everything else in the methods (excepting things relating to causal inference) seem fine.

The idea behind it, though, is to estimate how many people wouldn’t have had sudden cardiac arrest if the exposures didn’t exist, that is, if everyone were employed, rich, had high level qualifications etc.

Perfectly reasonable situation, if you ask me.

Results: observational analysis

Over a median of 13.8 years of follow-up, 3,147 (0.63%) of participants had a sudden cardiac arrest. The Cox regression results are in the paper, and shown below:

Note again that HRs above 1 mean the exposure is bad (the exposure is the first thing in brackets, so not employed, poor, low qualifications etc.), and below 1 is good. So, for instance, unemployment is pretty bad: a HR of 2.24 means, proportionately, many more people who were unemployed had sudden cardiac arrest compared with people who were employed. Smoking is also pretty bad (HR = 2.12), and “more” days and/or week” of vigorous physical activity is good (HR = 0.68)!

Normally, I’d also talk about the imprecision of these results, but a) all confidence intervals are reasonably tight, since they have to be to have a p<0.0004 and there were 500,000 people in each analysis, and b) the numbers of pretty meaningless, and I don’t want to dwell on them.

I should also note that these exposures were only at one timepoint between 2006 and 2010: they weren’t updated over time, they’re all just baseline measurements.

Note that income isn’t amongst the exposures. It was measured, but only in extremely broad categories. I don’t know how they handled it in the analysis (it may be in a supplement, but that’s sooo much effort…), but the best they could have done would likely have been more than £100,000 versus less than £100,000, and it wouldn’t have handled retired people well. And, of course, has only a passing familiarity with wealth over time, which would have been an extremely interesting exposure.

Let’s take a quick tally of which exposures we think are “modifiable” and which aren’t (I’ll skip lots):

- Physical activity: modifiable

- TV time: modifiable

- Computer time: more modifiable in 2006 to 2010 I’d think – how many jobs don’t involve computers now?

- Sleep duration: um… partly modifiable? Maybe? Depends?

- It’s easy getting up in the morning: um… I’ll go with not hugely modifiable for this I think

- Sleepless and/or insomnia: c’mon, really? not modifiable

- Current tobacco smoking: modifiable

- Past tobacco smoking: not modifiable, by definition

- Worry too long after embarrassment: what?

- Air pollution: how much money will it take to modify all these?

- Forced expiratory volume: wouldn’t you need new lungs to modify this meaningfully?

- Qualifications: modifiable, technically, I guess, but with what’s happening with the UK higher education sector, I’ll go with not massively modifiable

- Townsend deprivation index (poor vs rich): this is actually a relative measure – you could uplift everyone everywhere by the same amount, and the index wouldn’t change, because it’s based on relatively affluence by postcode. So, not modifiable

- Employment: modifiable – and easily too, right? Just give everyone satisfying jobs! Job done (ha, pun)

This isn’t a list of modifiable risk factors, this is simply a list of risk factors. With which, you can predict someone’s future risk of sudden cardiac death.

That’s all this analysis, as well as the population attributable risk analysis, tells us.

And it’s the same shit it’s always been: be rich, eat well, don’t smoke.

The only interesting this here is that the alcohol variables came out as “more alcohol is better than less alcohol”. This is what prompted the headline from The Guardian, although they got even that wrong, the exposure was “Average weekly champagne plus white wine intake”, and chances are, white wine dominated that particular variable.

And even that isn’t too interesting: it’s well known there’s a J-shape association between observed alcohol intake and cardiovascular outcomes – this is the premise behind “a glass of red wine a day is good for you!”. Any observed protective effect of alcohol on cardiovascular health is almost certainly biased: alcohol isn’t good for you. Sorry. I wrote a post about it here: it’s a little pissy.

Note: alcohol doesn’t have to be good for you, health wise, to be enjoyed. Don’t drink too much, enjoy yourself, great, have fun: but it’s probably not doing your heart any favours.

But there’s something almost all these exposures have in common: they are markers of wealth. Virtually none of these exposures couldn’t be improved by being richer:

- Want more time to exercise? Be richer.

- Want more sleep? Be richer.

- Want to nap during the day? Be richer.

- Want more education, and more or less of everything else that education affects? Be richer.

- Want to be richer? Be richer.

There’s no accounting for wealth in this analysis, and it affects everything. There is no possible way to interpret this analysis causally. It would be insanity to take any action on the basis of these results, other than to acknowledge that wealth matters to health.

Results: Mendelian randomization analysis

The point of Mendelian randomization analysis is to be able to obviate one of the biggest problems with observational analyses: done correctly, with the right exposures, you can reduce (or remove) the risk of confounding. So, done perfectly, you could remove the effect of wealth that is messing with the results above. Possibly. It’s hard.

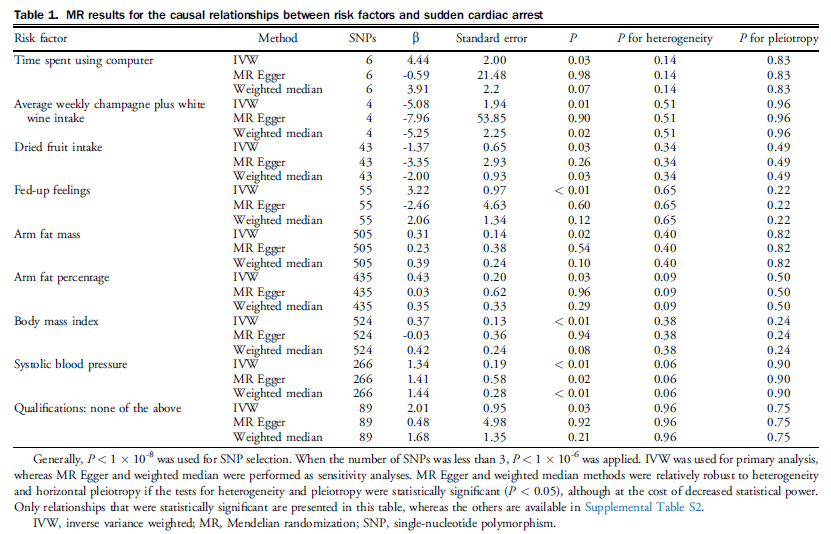

Table 1 in the paper gives a selection of Mendelian randomization results. There are 3 methods per exposure to test the Mendelian randomization assumptions: you’re looking for consistent results between the methods (it doesn’t matter if the P values are different). These are just the statistically significant results (p<0.05 this time: Mendelian randomization sacrifices a lot of statistical power in exchange for the ability to make more causal claims [depending on the exposure…]).

The authors claim: “Among the 56 risk factors identified through EWAS, MR analysis further identified 9 exposures causally related to SCA” on the basis of these results.

Remember I said that Mendelian randomization is best when the exposure is as close to a protein as possible, otherwise it can be biased?

Well, I’m going to say that these exposures are not close to a protein, and so are highly likely to be incredible biased:

- Time spent using a computer

- Average weekly champagne plus white wine intake

- Dried fruit intake

- Fed-up feelings (depression does have a genetic component, but this isn’t depression)

- Arm fat mass (less certain about this – may be related to body mass index? But… How is this modifiable?)

- Arm fat percentage (as above)

- Qualifications (one of the problems with Mendelian randomization is assortative mating: that is, people don’t procreate with random partners, but with people who are similar to them. This is problematic for qualifications, which is also heavily socially patterned. And it doesn’t matter how genetically smart you are if you never have the opportunity to excel in school, for instance. Basically, I’m dubious these 89 SNPs only affect qualifications)

I’m more happy with body mass index and systolic blood pressure: anthropometric measures like this can be quite closely related to individual proteins (though biases may still remain).

So, of these results, I think they’ve shown that there might be a causal effect of body mass index and systolic blood pressure on sudden cardiac death. And… Yeah. No shit. Well fucking done. Who knew? Apart from fucking everyone.

The remaining exposures are way too far away from proteins to have any confidence in the Mendelian randomization results. The only way for my to have any confidence would be for someone to explain the mechanism behind how those SNPs affect those exposures, and only those exposures.

How, precisely, do those 6 SNPs affect time spent in front of a computer?

How do those 4 SNPs affect, specifically, white wine and champagne intake? Do they affect red wine intake? Beer? Cider? Port? Vermouth? Amarula, the fruit of the elephant tree?

And the same for the remaining exposures.

Without those explanations, I have no confidence these results are causal. They are just as likely to be biased as the observational results above!

Causality is hard!

Summary

Here’s the thing: there was no point to this study.

The authors wanted to assess causality, but the observational analysis cannot be causal, because, among other things, wealth over time cannot be accounted for, and affects everything. The Mendelian randomization analysis, as I explain above, is only likely to be causal (and even then, barely), for body mass index and systolic blood pressure, two exposures we already know are implicated in heart health.

The population attributable risk analysis is irrelevant if the data going into it is non-causal. Here, the question is “what would happen if I changed the exposure?”, and to answer that question, you need causal effects. Without that, you can’t say anything about what would happen if you changed the exposure.

So: “What would happen if everyone drank more white wine and champagne?“

People who produce white wine and champagne would become richer.

And… That’s it. That’s what we’ve learned from this paper.

I do have some sympathy with the authors: I wrote a similar paper using very similar methods in the same population looking at: “The causal effects of health conditions and risk factors on social and socioeconomic outcomes: Mendelian randomization in UK Biobank” (I also wrote a blog post on it).

The exposures here were health conditions and reasonably genetically patterned risk factors for poor health (alcohol intake [across all alcoholic drinks, not just “white wine”], body mass index, smoking, systolic blood pressure), and the outcomes were social and socioeconomic. Were the results causal? Maybe not massively causal, but because we used health conditions (most or all of which were known to have genetic determinants) and risk factors (ditto) as the exposures, we had a higher chance of causality than using behaviours as the exposures.

Nonetheless, it was a similar analysis, so I have some sympathy for the authors for the paper. We even had similar heat maps (mine on the left, theirs on the right):

But.

Their analysis was pointless.

They wrote about and promoted their work as causal.

They gave false hope by stating that at least 40% of sudden cardiac arrests could be prevented through modifying these exposures, many of which were unmodifiable (or horrendously difficult to modify).

I assume their university did a press release (otherwise, I don’t know why The Guardian would have picked it up), and the media promoted their work.

In sum: I think they have probably done more harm than good.

This is the shit that makes people despair of observational epidemiology.

But, you know, maybe those poor champagne makers will be able to sell a few more bottles.

So that’s… Good.